Hang Ah Alley and 'Chinese Playground: A Memoir'

Hang Ah Alley

Janice and I spent Thursday mid-morning walking around Hang Ah Alley which is next to the Chinese Playground. Although the Alley was not crowded with people, we could hear the sound of Mah Jong tiles coming from the Benevolent Family Associations situated on the side of the Alley opposite the Chinese Playground. Peeking through half open doors, I saw the older folks playing Mah Jong in all three benevolent associations.

Older folks playing mahjong at the Wong Han Benevolent Association

We stopped for a light snack at the Hang Ah Tea Room, which claimed to be the oldest place in Chinatown selling dim sum. Having much publicity from travel guide books and travel agents, the Hang Ah Tea Room has turned into a tourist attraction and a place where the Chinese brought business associates. This was probably a place where a local would never step in for a meal, and the crowd in the Tea Room was comprised of foreigners or Chinese with foreign business associates.

Outside the Hang Ah Tea Room

After a light dim sum, we returned to the Chinese Playground which Victor had brought us to last week for a quick visit of the place. I remembered that I didn’t have much of an impression of the playground, just that it was a place for recreation and where parents brought their children to play during the weekends. The official inscription pinned on the building where Hang Ah Alley was read:

Hang Ah Alley

The Chinese Playground is one of the few recreational facilities in Chinatown. In order to make use of as much open space as possible, the Committee for Better Parks and Recreation in Chinatown and the San Francisco Department of Parks and Recreation worked for 11 years on new plans for the playground. The old club house was torn down in June of 1977 and the new structures were installed 3 years later. Mr Oliver C. Chang was the first director of the Chinese playground as well as the first Chinese American director of the SF Department of Park and Recreation.

The Chinese Playground for me has taken on a different meaning after reading more into the Chinese street gangs and picking up the book ‘Chinese Playground: A Memoir’, written by a Chiense ex-gang member, Bill Lee. As a tourist, one would have never suspected that the Chinese Playground reflected both the wholesome and the underlying social ills of the Chinese community, especially during the 1960s and 1970s.

The Chinese Playground after the 1977 refurbishment, also known as the Willy 'Woo Woo' Wong Playground

“The city of San Francisco purchased the land in 1925 and completed construction in 1927. The playground was situated with Waverly Alley to the east, Hang Ah Alley to the west and Clay and Sacramento streets as its north and south borders, respectively. There were three levels within the grounds. A basketball court was on the lower level, and a tennis and volleyball court were in the upper section. Everything was out in the open. A small clubhouse with a pagoda design stood on the main level along with a slide, swings, merry-go-round, and ring apparatus.

I spent countless hours playing ping pong on a table that was bolted to the ground in front of the clubhouse. Every few years, they’d slap a new table-top on. Behind the building sat a mini-slide and concrete sandbox where we transported water for our muddy-duddy creations. There were three ways to enter and exit the park: from the two alleys and on Sacramento Street. The multiple accesses served us well as children playing hide-and-seek. The playground was our home base and we hid throughout Chinatown.

As a young boy, I was chased by the police in one entrance and out the other over illegal fireworks sales or other petty crimes.

The first gang of immigrant kids, the Wah Chings, originated out of this playground in 1964, complete with club jackets. They discreetly came in ad out through Waverly Alley and congregated in the basketball court that they used for soccer. Every Sunday afternoon, an organized volleyball game was played in which gang members participated with others from their homeland.

The gang wars from the late sixties to the late seventies turned the playground into a hot spot. It symbolized the ruling gang in Chinatown, and opposing sides ambushed one another at all entrances. Chinese Playground was a second home to me from the time I was a toddler. Just half a block from our house, it was reached by crossing one intersection to Hang Ah Alley. Kids gathered there early in the day on weekends, holidays, and during the summer. We also played in alley ways, jumped on and off moving cable cars and hung around department stores downtown. But at the end of each day, we regrouped at the playground.”

Having an understanding of how Tongs work in the Chinese American community is crucial. Chinese gangs (Tongs) are part and parcel of the Chinese American Community in San Francisco. Much of the newspaper cuttings which we read from the San Francisco Chronicle about the recent gang violence and shootings seem to suggest that the underside of the Chinese American Community living in San Francisco have to grapple with. Although gang activities are not as rampant as they were in the 1970s, much of the Chinese American community today speaks little of the topic for fear of retaliation by these gang members. In this book, street gangs do recruit members from the recreational areas, thus park directors cannot be caught off guard and it was part of their everyday job to have to interact with teenage gang youth. Thus, park directors were held in high regards and as Lee puts it, “most of the kids who hung out at the playground spent more time with Paul (the site director at that time) than with their own parents. He was firm, yet highly skilled in diplomacy, earning respect from fei jies (gangsters) who were fearless).”

In Lee’s opinion, the playground “wasn’t a conducive place for any child to be in. Adults who chaperoned their children there enjoyed the facility as it was intended. But it was, for the most part, comprised of kids from troubled homes thrown together unsupervised. Paul (the site director) was a good influence, but he was one person. Junior sociopaths outnumbered him twenty to one.

We didn’t develop the right social skills at Chinese Playground. The environment represented the dark side. We learned to cheat and lie. What you could get away with prevailed over fair play. It was ‘screw the other guy first’ and ‘you don’t let anyone fuck with you’.”

Nevertheless, street gangs are less prevalent in the playground after its refurbishment in 1977. When Janice and I were in the playground that morning, we came across a group of old Chinese men who were playing table tennis. We met with Mr Luo, 75. We introduced ourselves as Singaporeans, and he said that he and LKY were from the same province. He told us that he was a table tennis coach who coached in the Chinese Playground and that his whole family was here in the bay Area.

Inside the Chinese playground clubhouse, old men playing table tennis

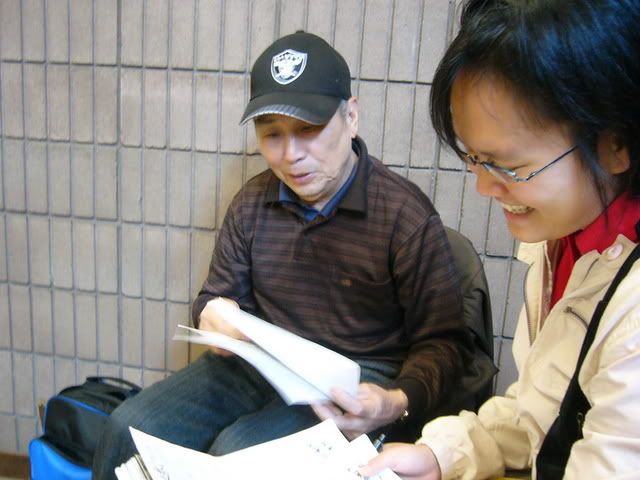

Janice and Mr Luo

Mr Luo showed us some of his photos of his family. Being a table tennis coach, he told us that he wrote a sports anthem which he used for his team during competitions. The anthem:

人生什么 最难忘 骨肉情深 最难忘

人生什么 最重要 保养好身件 最重要

读书 为 的是什么 读书 为 事业 为前途

多 少数的守候 多少辛筋的关爱

人生什么 最快乐歌唱我们的新生活

海外的亲人常思念,唉咳喻。。。 终于回到自己的守园

强身健体要坚持,唉咳喻。。。身体强健才 有夺钱

筋学苦练为自己,唉咳喻。。。 前途光明才有出息

养育着你们步步的成长,唉咳喻。。。是爸 妈恩情忘不了

祝愿 早日完成祖国 一大业,唉咳喻。。。 祝庆我们全部欢聚在一堂

为献上我对会周年庆祝 而欢呼歌唱吧!

罗威

Hang Ah Alley, written by Steph

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home